英语原文共 3 页

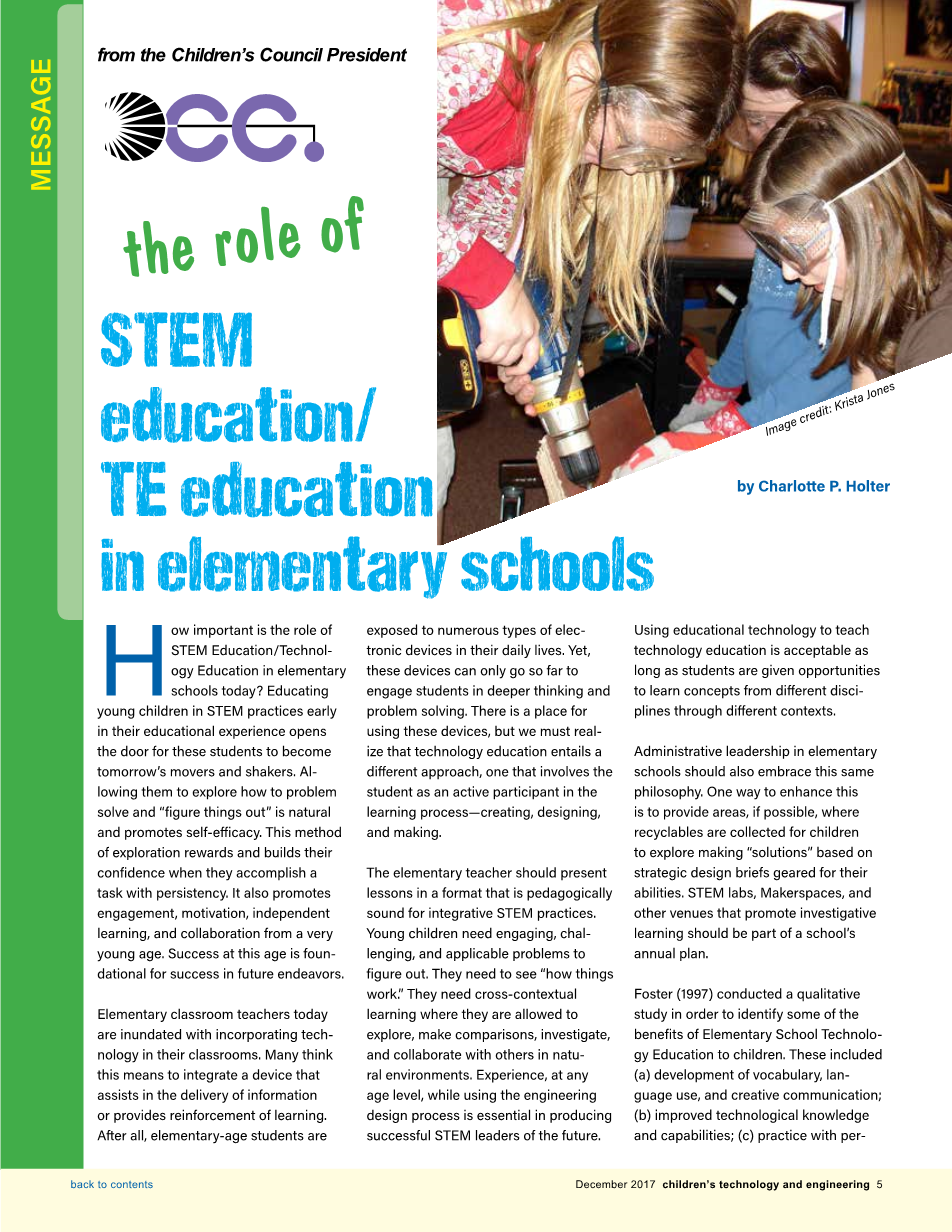

STEM教育/技术教育在当今小学教育中的作用有多重要?

在孩子的教育中为他们打开一扇STEM实践的大门,让他们成为明天的推动者和影响者。让他们觉得去探索如何解决问题和“把事情弄清楚”是很自然的,并能提高自我效能感。当他们坚持不懈地完成一项任务时,这种探索的方法会给他们带来回报,并帮助他们建立信心。还能从很小的时候就促进学生的参与、激励、自主学习和合作的能力。在这个年龄取得的成功将是未来成功的基础。

如今,小学教师的课堂上充斥着各种各样的科技产品。许多人认为,这意味着要集成一种帮助传递信息或加强学习的设备。然而,这些设备只能让学生进行更深层次的思考和问题解决。使用这些设备是有效的,但我们必须认识到,技术教育需要一种不同的方法,一种让学生积极参与学习过程的方法——创造、设计和制作。

小学教师应该以一种适合STEM综合实践教学的形式授课。幼儿需要参与挑战和选择适用的问题来解决。他们需要看到“事情是如何运作的”。“他们需要跨语境的学习,这样他们就可以在自然环境中探索、比较、调查和与他人合作。利用教育技术进行技术教育是可以接受的,只要学生有机会通过不同的背景学习不同学科的概念。

小学的行政领导也应该遵循同样的理念。提高这一能力的一种方法是,如果可能的话,为孩子们提供可长期使用的场所,让他们探索适合他们能力的战略设计简报来制定“解决方案”。STEM实验室、创客空间和其他促进研究性学习的场所应该成为学校年度计划的一部分。

福斯特(1997)进行了一项定性研究,以确定小学技术教育对儿童的一些好处。这些措施包括

(a)发展词汇、语言使用和创造性交流;

(b)改进技术知识和能力;

(c)用per-练习认知和运动技能,以及图形表示、可视化、设计和工具使用等技能;

(d)提高社会和生活技能,如参与、责任、个人成长和与他人合作的能力。

从技术上讲,我们在过去几年中经历的教育向数字化的过渡给我们带来了新的挑战。然而,它帮助我们认识到考虑学生整体学习经验的重要性,以及我们如何才能使未来变得更好。小学是开始这一有益之旅的地方。

译文二:

Collaborative Creativity in STEAM- Narratives of Art Education Students#39; Experiences in Transdisciplinary Spaces

Abstract

Current efforts to promote STEAM (STEM Arts) education focus predominantly on how partnering with the arts provides a range of benefits to STEM students. Here we take a different approach and focus on what art and art education students stand to gain from collaborating with STEM students. Drawing on a variety of student field texts, we present three visual-verbal, constructed narratives of art education students who, in the context of a transdisciplinary design studio, were challenged to experiment with collaborative forms of creative thinking. Their stories point to STEAM as an opportunity for art students to question the notion of the lsquo;lone artist,rsquo; reflect upon the tension between product and process, and expand disciplinary-based understandings of creative thinking. These potential benefits align with contemporary visual arts practices that strive to move beyond the individual and embrace dialogue, collaborative action, and interdisciplinarity as vital aspects of the creative process.

I like the idea of collaborationhellip;because it pushes youhellip;

It#39;s a richer experiencehellip;.

Frank Gehry (2008)

As an art educator, I am relentlessly intrigued by the idea of creativity. Both engaging in artmaking and watching others create over the years has impelled me to consider how individuals conceive of creativity, how they see themselves as creative beings and, perhaps most importantly from my perspective as an educator, the facets of what and how we teach as supporting studentsrsquo; creative development. During the fall of 2012, I was afforded the opportunity to teach, along with co-author Nicki Sochacka, a STEAM (an acronym for Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics)-inspired course referred to as the Transdisciplinary Design Studio at a research university in the southeastern United States. It was in the context of this formative experience that I, as both a teacher and researcher with an interest in visual-verbal methods of analysis, became attuned to the notion of collaborative creativity—how individualsrsquo; creative processes enmesh and collide as they endeavor to reach new and shared understandings. In particular, when the semester ended and I began to analyze the studentsrsquo; field texts as part of my dissertation research, I was provoked by the way the creative process, often characterized and understood as an individual pursuit, was described by many of the students as a collective action that emerged as they explored design challenges within interdisciplinary groups. Perhaps it is unsurprising that this notion was not immediately visible to Nicki and me while we taught the design studio. As Eisner (1960) pointed out, it is difficult to see the creative process “qua process” (p. 28). Instead, he wrote: “We must infer the nature of the process from what we can observe” (ibid.). In line with Eisner, it was through a post factum visual-verbal analysis of a collection of the studentsrsquo; visual-verbal artifacts from the course that Nicki and I were able to observe the studentsrsquo; narratives of creativity and the creative process. These narratives painted a unique and unexpected picture of STEAM as a space that cultivated a collaborative approach to creativity.

In this article, my co-authors and I draw on a variety of student field texts to present three visual-verbal, constructed narratives of art education students who, in the context of the Transdisciplinary Design Studio, were challenged to experiment with collaborative forms of creative thinking. This unique visual-verbal methodological approach (Guyotte, 2013) afforded us the opportunity to consider how students told stories of their interdisciplinary collaborative experiences and how those experiences impacted their perceptions of creativity. Their stories have important implications for art educators, proponents of STEAM education and, more broadly, for society where the need to find collaborative and creative solutions to complex challenges is becoming increasingly critical.

Collaborative Creativity

The belief that learning is a sociocultural and co-constructed activity (Vygotsky, 1978) is often cited as the impetus for fostering collaboration in the classroom. Through such collaboration, students bring together varied life experiences, knowledge, and approaches to meaning making in the shared pursuit of a learning goal often put forth by the instructor. While the notion of collaboration is not new in educational contexts, it does stand in contrast to many traditional perceptions of the visual arts in higher education. In these disciplinary experiences, students often speak of autonomy in their studio courses—retelling the longstanding narrative of the lone artist, physically or mentally isolated, deeply engaged in her/his own creative process (Thomas amp; Chan, 2013). This perception may be rooted deeply in the American ps

以上是毕业论文外文翻译,课题毕业论文、任务书、文献综述、开题报告、程序设计、图纸设计等资料可联系客服协助查找。